Norwich’s Over-the-Water district was once the centre of the weaving industry. Between 1650 and 1750, most weavers’ premises were concentrated there. Right up to the end of the nineteenth century, trade directories named 44 weavers and manufacturers in the Magdalen Street area and there were undoubtedly many more.

In the second half of the sixteenth century Low Country weavers (The Strangers) came to Norwich and revitalized weaving. They introduced what were called the New Draperies. These developed into distinctive worsted textiles in the seventeenth century, known as the Norwich Stuffs. Introducing the drawloom, the Strangers designed colourful and very varied fabrics, with flower patterns, checks and shaded stripes for a middle class market of minor gentry and merchants. Although creating mainly worsted cloth, many used other yarns, including mohair, silk, and linen. Their designs and skills were adapted quickly by local weavers.

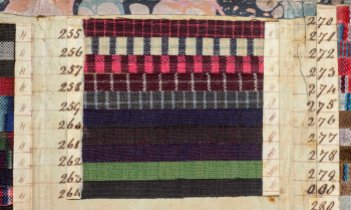

A strength of the specialist trade was the ability of the master weavers to diversify fabrics in line with changing tastes. By the end of the seventeenth century, Norwich was the centre for ‘half-silks’ (a mixture of silk and worsted). By 1750 Norwich weavers produced a huge diversity of texture, weave and pattern using worsted yarns of very high quality, dyed in a range of bright colours. These fabrics had a variety of exotic names: tapizadoes, taboretts, camblets and callimancoes. Later, in the nineteenth century, Norwich also became known for mourning fabrics – Norwich crepes and bombazines and renowned at home and abroad, the Norwich shawl.

A page from an order book from the 1760s (photo P.Harley. Courtesy Norwich Museum Service)

A page from an order book from the 1760s (photo P.Harley. Courtesy Norwich Museum Service)

Structure of the business:

Historically, Norwich was a city of small and medium-sized businesses, each one an independent, self-financing, family based operation with only a few looms. Typically the owner was a master weaver who would keep an eye on all aspects of manufacture and who would find a buyer for the goods himself. In the 1750s this pattern changed. Capital had accumulated as the trade expanded, especially in exports; firms merged and became larger and fewer.

The manufacturer’s residence was the hub of the operation. It was usually a handsome house with a counting house, packing rooms warehouses and a hot- pressing shop to the rear. In a skilled process, the hot-press was applied to some products to give the cloth a high gloss. The cloth was pressed by a screw press, which compressed cardboard with gum Arabic and the cloth underneath. The smooth glaze was fashionable. This process also concealed flaws in the weaving. Spinning, weaving and dyeing generally took place in people’s homes. The manufacturer could employ as many as 300-400 weavers who were paid piece rates and worked at home. Obviously, this took a lot of organization.

The long, fine, white worsted weaving wool came mainly from Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire and Leicestershire, with some coming from the Yare valley. For eight months of the year, following the first shearing in March, buyers bought up the wool clip and sent it by packhorse and canal to Boston where it was shipped to Kings Lynn and Great Yarmouth.

First it went to the woolcombers who pulled heated iron combs through it to smooth away the tangles, a skilled job, though hot and dirty. The spinners received the combed wool next and carts dropped it off within a rough radius of 20 miles of Norwich. Spinning tended to be part-time and done at home on a distaff and spindle (rather than a wheel which produced a thicker thread).

The only record of the dyeing process is from Sharps London Magazine March 1847: ‘The dye house is at least 150 feet long, under one roof, streams of liquid dye which discharge from the numerous vats are constantly pouring along and in the centre of the floor – woolen yarns, scour in ammonia and soap spun silks toss in boiling water. Loops of yarn hang dripping from dyers pins and are dipt in vats and boilers. The vats are cast iron, 6 and a 1/2 feet deep.’ Think of the stench and river pollution.

‘Norwich Red’- (first mentioned in 1759 in the obituary of Ben Elder in the Norwich Mercury) became famous. Michael Stark, a Scotsman, living in the city, was a noted chemist who succeeded in producing a very fine scarlet, which dyed both wool and silk the same colour, something that hadn’t been achieved before. Edinburgh manufacturers sent silk to be dyed crimson or red, south to Norwich which became for a time the main supplier of tartans to the Scottish regiments.

Red damask (described as a ‘sattin’) madder dyed (photo P.Harley. Courtesy Norwich Museum Service)

Red damask (described as a ‘sattin’) madder dyed (photo P.Harley. Courtesy Norwich Museum Service)

A weaver then wove the cloth before it was sold on to the merchant. In most cases the weaver was a journeyman who had completed his apprenticeship (usually started at 11 or 12) but could not find the money to set up his own business (or didn’t have the ambition or inclination to set up as a master). For much of the eighteenth century the terms weaver and manufacturer were interchangeable. By the nineteenth century manufacturer seems to apply to the employers of the weavers. The process of setting up the loom for the increasingly complex patterns was of utmost importance and it is probable that in most cases it was done by master weavers.

Manufacturers/employers needed houses or warehouses large enough to store yarn, possibly with a space for a designer. Fringers and sewers could work from home or in a part of the warehouse. Last of all was the hot presser who gave the cloth a stiff glaze.

Exports

The eighteenth century was the ‘golden age’ of Norwich weaving. It brought wealth to many of the master-weavers like the Ives and the Harvey families who built some of the fine houses on Colegate. Jeremiah Ives later moved out of the city to Catton Hall.

The export of ‘Norwich stuffs’ grew rapidly. The cheaper stuffs (which were often glazed by the hot-press) were popular in central and northern Germany and the Baltic in the ‘peasant’ market (what we might think of as folk costume today). In the 1760s the trade expanded to Poland and Russia where callimancoes became popular among Tartar and Siberian tribes. In Italy lighter cloths sold well and there was a growing market in Spain and Portugal, where some were exported to Mexico, the West Indies and the Americas. There were also regular orders from the East India Company for camblets in India and the Far East. Much of the export industry was conducted from London, four days away along the ‘good’ turnpike road.

Striped calamanco 1760s (photo P.Harley. Courtesy Norwich Museum Service)

Striped calamanco 1760s (photo P.Harley. Courtesy Norwich Museum Service)

In the 1760s some Master weavers wanted to cut out the profits made in London (and also the occasional bottlenecks which affected the industry in Norwich) and they began to contact foreign firms directly. William Taylor, a German scholar, writer and visitor to the city says ‘their travellers penetrated through Europe and their pattern books were exhibited in every principal town from the frozen plains of Moscow to the milder climes of Lisbon, Seville, and Naples…The great fairs of Frankfort, Leipsic (sic), and of Salerno, were thronged with the purchasers of these (Norwich) commodities’. The Masters of Norwich travelled abroad and foreign buyers visited the city. The elegant houses of this increasingly sophisticated class can be seen in Colegate, St Giles, and their beneficence can be seen in the construction of the Octagon Chapel, created from textile riches.

Threats to Norwich Industry:

Foreign wars in 1760s and 70s brought setbacks and an end to growth. In 1762 the Spanish trade was disrupted by war with Spain, and because the London warehouses had stockpiled Norwich stuffs there were cutbacks in production in Norwich, lay-offs and unemployment. The American War of Independence (1775-83) caused a lot of damage to the industry.

At home there was an increasing threat from cotton production in Lancashire, cotton goods being cheaper, readily available and easily washed (unlike the glazed Norwich stuffs).

Another threat was from the West Riding of Yorkshire where a northern worsted trade was rapidly developing (producing coarser and simpler stuffs) exporting from Hull. Towards the end of the century Halifax in particular started copying good quality versions of Norwich’s bombazines, camblets and damasks and tempted some Norwich weavers north to help in their development.

Trade picked up at the end of the American War and huge orders from the East India Company followed. Legend has it that happy weavers flaunted their riches with £5 notes in their hat-bands (reminding me of Ipswich supporters waving £20 notes at Norwich fans after Marcus Evans purchased the club).

The revolutionary wars with France (1793-1815) and the Continental Blockade put an end to trade with Europe. Foreign trade was maintained through exports to Asia and the Far East through the East India Company, which ordered between 16,000 and 24,000 camblets annually between 1800 and 1815. When the East India Company lost its monopoly in 1813, exporters started using the cheaper Yorkshire camblets. Meanwhile the highly specialised Norwich shawl, sold mainly in the home market, helped to alleviate some of the effects of the downturns in trade.

Industrialisation and mechanisation.

Norwich’s distance from the coalfields and all the technical innovation that was going on around them, put the city at a disadvantage. The invention of the throstle, for the mechanical spinning of worsted completely by-passed Norwich, East Anglia and Ireland, which sent a lot of yarn to Norwich. Machine spun yarn was far more consistent in quality than hand spun. After 1819, Norwich manufacturers turned to Yorkshire for yarn and the local spinning industry, employing 20,000 women and girls of the city and surrounding countryside, collapsed within 5 years.

There was no attempt to manufacture machine spun yarn in the city until 1834 when the Albion Mill (still standing and now converted to apartments) was built on King Street. It was followed by the St James factory at Whitefriars (The Norwich Yarn Company), which had steam power and six floors to rent to producers who supplied their own machinery. But it was already too late.

Norwich also missed out on the development of the power loom after 1825, and the weavers lost the production of many plain worsteds to Yorkshire in the 1820s and 30s. Further developments in mechanisation in the 1840s and 50s were centred on Bradford but were not taken up in Norwich.

Pattern book detail, late eighteenth century (photo P.Harley. Courtesy Norwich Museum Service)

Pattern book detail, late eighteenth century (photo P.Harley. Courtesy Norwich Museum Service)

From the 1820s the textile trade in Norwich became increasingly specialised (mainly shawls and bombazines – see below) but even here there was fierce competition from Paisley and abroad. Of 850,000 spindles and 32,600 power looms at work in 1850, Norfolk possessed 19,216 and 428 respectively. Hand weaving could not compete with the cheaper mass-produced products in cotton and wool from Lancashire and Yorkshire.

Reaction of the weavers

The Norwich weavers resisted mechanization. They were a close-knit community and the workers had a well-earned reputation for organized rioting and violence to combat changes that affected their livelihood.

In 1790 (just before the French wars), when trade was booming, wage rates were fixed by agreement with employers and posted up in workplaces. This arrangement remained in force for some years and was firmly insisted on by the Weavers’ Committee, whatever the conditions of trade. When trade took a massive downturn during the French wars, any suggestion that wages should drop during difficult economic times was resisted by strikes and violent threats – another reason for the employers’ reluctance to introduce machinery.

The Norwich industry went through a protracted depression from 1825-37. By the 1830s most commentators reckoned that the average weaver was likely to be out of work for about 3 months a year. There were constant attempts to cut wages in line with severe price falls. 1828-1829 were particularly bad years when two bombazine manufacturers went bust, including the Martineaus. Selective wage reductions were broached and backed by the Court of Guardians. The weavers finally marched on the house of the chairman of the court, broke his windows and pulled down his gate. The 7th Dragoon Guards were called in to suppress the riot. And a wage reduction of 20% was put in place.

In 1830 John Wright, described in the local press as ‘one of the most considerable master manufacturers’ had vitriol thrown in his face as he arrived home. Four years earlier, weavers had attacked his house and destroyed yarn which he was sending to the countryside (for weaving at a cheaper rate). By 1838 Wymondham, a small town, 10 miles from Norwich, had 300 looms operated at cheaper prices than Norwich. There were many other instances of intimidation. Some of the master weavers left the industry – the Gurneys went into banking and the Pattesons into brewing.

The 1838 reports of the Assistant Commissioner on Hand Loom Weavers gives an insight into the sorry state of many hand-loom weavers and the industry as a whole (and not just in East Anglia). The manufacturers laid the blame for failure to mechanise on the weavers as did the commissioner, Dr Mitchell.

But the weavers very way of life had been challenged by the constant underemployment, declining piece rates and the threat of the power loom. The 1838 report also showed how things were changing. There were fewer looms and more than a quarter were operated by women at cheaper rates. There were still 3398 looms worked in homes and 656 in factories. There were 8 textile factories employing 1,285 people using 151 steam horsepower.

These changes in the weaving industry were exacerbated by wider changes. In Norfolk, the mechanisation of agriculture displaced labour and many workers migrated to the city seeking work at almost any wage. The population of the city rose from 37,000 in 1801 to 68,000 in 1852. Living conditions were dreadful for many workers.

Developments in Norwich weaving in the nineteenth century

Developments in the early nineteenth century kept the industry afloat, in particular the Norwich shawl. Fashionable shawls were very expensive imports from Kashmir, using soft and silky wool from the Tibetan goat. Manufacturers in Norwich tried to make a similar item, only cheaper.

In 1792 Alderman John Harvey of Colegate, with P.J.Knights succeeded in weaving a seamless 12 foot wide shawl on a silk warp called a fillover shawl, because it was embroidered or filled in by women and children. By 1802 it was possible to weave the design on the loom rather than embroider it by hand. Shawls woven on the fillover loom could fetch prices from 12 to 20 guineas with the most complex designs and the finest weaving fetching 50 guineas (a guinea is £1.05p). A weaver, working at home in 1850 might be earning 45p a week, working in summer a sixteen hour day and in winter a fourteen and a half hour day.

A further development was the Jacquard loom (which was far too big for most weavers’ homes). This cut down on labour as it used punched cards instead of the nimble fingers of a draw boy. The first one used in Norwich was probably in 1829 or 1830 by Willett and Nephew.

Some of the shawls had designs printed on them (usually making them cheaper). The ones printed on leno or muslim were worn with light summer dresses. The shawls became renowned worldwide for their superb design, quality and workmanship, and sold for high prices, earning good wages when trade was good.

By the late 1840s and 50s there were at least 28 manufacturers making shawls of different types in the city. The order book of E&F Hinde in 1849 gives some indication of numbers: 26 types of shawl and 39,000 orders for the year. The Arab (either in Low, High or Superior) appears to be a semi-circular shawl with a mock hood and tassel on the straight side.

Shawl production was at its height in the 1850s. In the 1860s and 70s the firm of Clabburn, Son & Crisp created what were considered to be some of the finest of Norwich shawls made entirely of silk. The designs were flowing and have a strong feeling of Art Nouveau. Many shawls were things of beauty which carried off prizes at international exhibitions and had a reputation for quality. However, they were subject to the vagaries of fashion and competition especially from Paisley printed shawls which were cheaper and machine made. By 1870 shawls were no longer in vogue and there were only nine firms making them, in contrast to the thirty- four recorded in the 1790s.

Alongside shawls, other businesses sprang up making crepes and bombazines (for mourning). Bombazine was a silk and worsted mix made in a twill weave to give densely black appearance. Gauzes were made from pure silk. The first was invented by Mr Francis (of Calvert Street) in 1819 and christened Norwich crepe. It was of a silk and wool mix but highly coloured and finished to look like satin. Mourning clothes provided a relatively steady market in contrast to the vagaries of the fashion trade in coloured stuffs.

In 1822 Joseph Grout (first noted 1807, Paterson Yard, Magdalen Street) introduced the modern Norwich crepe (sometimes spelt crape, as in the Norwich Crape Factory established in St Augustine’s by Henry Willet and John Sultzer). Crepe was designed specifically for mourning, and made from twisted silk yarn, woven into a fine gauze, dyed black, stiffened with shellac and embossed with patterns by means of a special and at first secret crimping machine. It was the ‘quintessential expression of Victorian grief’ and made in enormous quantities. Widows were expected to wear full mourning dress for two years and there were various stipulations for family members depending on the relationship to the deceased. Grout’s business developed and was probably helped by Queen Victoria’s patronage. Thhe Company expanded to works in New Mills, Lower Westwick Street, warehouses in London and production around East Anglia (Great Yarmouth and North Walsham in Norfolk). It was said to be the largest of its kind in the country. He also used steam power in his mills. The Norwich Crape Company closed in the 1920s, finally hit by the decline in mourning ritual.

Glazed damask from a pattern book

Glazed damask from a pattern book

The weaving trade had revived by 1850, but was much reduced from its former glory and by the 1870s shawls went out of fashion. In 1875, The National Mourning Reform Association was set up to campaign for ‘moderation’ and ‘simplicity’ instead of ‘unnecessary show’ in mourning attire. The skills of the Norwich weavers were overtaken by the whims of fashion and mass-production. A mark of the decline is that in 1851 almost 33% of the workforce (both men and women) was employed in the textile trade. By 1901 it was less than 7%. Many weavers had gone into the rapidly developing leather and shoe industry.

Sources:

Norwich in the Nineteenth Century. Editor Christopher Barringer. Gliddon Books, 1984

The Norwich Shawl. Clabburn P. HMSO 1995Norwich, City of Industries. Williams N, Norwich Heart 2013

Museums information sheet. The Norwich Shawl by Pamela Clabburn, 1975

Norwich since 1550. ed Rawcliffe and Wilson (Hambledon and London)

The Fabric of Stuffs. Ursula Priestley. Centre for East Anglian Studies, 1990

Why this research? Firstly my interest in textiles and local history (the research was mainly from the secondary sources mentioned above) and secondly to help inform the script and songs of a forthcoming production by The Common Lot – Anglia Square A Love Story which was performed in July 2019 in the streets of Norwich and Anglia Square – more information on the sites below.

https://thecommonlot.org/ https://angliasquarelovestory.com/

Thanks to Barbara McKeown for ironing out my English and spotting various errors.

Thanks to Ruth Battersby Tooke of the Norwich Museum Service and the Norwich Castle Study Centre study centre for showing me some of the textile collection and allowing me to photograph some of it for this article.

Do visit The Museum of Norwich which has a surviving Jacquard loom, pattern books from the eighteenth century and a skirt made from Norwich cloth. The Castle Museum has Norwich shawls in its Design for Living section.

https://www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/norwich-castle

https://www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/museum-of-norwich

https://www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/norwich-castle/whats-here/norwich-castle-study-centre

The photos in the gallery below were taken by me and are mainly of late eighteenth century textiles and pattern books.